August 10, 2016

Appealing for an Alternative: Ecology and Environmentalism in Joseph Beuys’ Projects of Social Sculpture

Written by Cara Jordan

In December 1978, the German artist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) published a public appeal, “Aufruf zur Alternative” (Appeal for an Alternative), in the cultural section of the Frankfurter Rundschau.[1] Widely cited as the artist’s manifesto in which he set forth the policies of the future Green Party, in the article he reiterates the ideals set forth by his previous projects dedicated to direct democracy and education reform, and insists that all Europeans demand a radical alternative to Western capitalism and Eastern communism. He further outlines the ways in which money and the state had caused a state of crisis in the postwar era: the threat of nuclear war, the destruction of the environment, consumer culture, overproduction of goods, and an inequality produced by state-control of the economy, all of which contribute to a “crisis of consciousness and meaning.” His solution is a “third way,” one by which society is organized by the individual through his own creative initiative, which he deemed “social sculpture.”

The concept of social sculpture, which Beuys developed in the early 1970s, centered on the belief that art could include the entire process of living — thoughts, actions, conversation, and objects — and therefore could be enacted by a wide range of people beyond artists.[2] Derived from his involvement with Fluxus, the theories of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, and his radical pedagogical approach at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, Beuys’ ideas reflect his desire to seek an alternative to the chaotic political, economic, and social life of a divided post-war Germany through a work of art with holistic and spiritual intentions. His projects of social sculpture, such as the Office for Direct Democracy and the Free International University, were part of his way to produce widespread social change through collective creative action while at the same time demonstrate his commitment to direct democracy, education, and environmentalism. Through these projects and his later initiatives such as his involvement with the green movement and 7,000 Oaks, Beuys hoped to create a model for artists to enact social and political transformation and to develop a “real alternative to the existing systems in the West and in the East.”[3]

Following a flurry of artistic activity in the immediate postwar period, which included his creation of his infamous fat and felt sculptures, performances with animal corpses, and participation in the international Fluxus group, by the late 1960s Beuys had begun to conceive of a second branch of his work — a “permanent conference” — which he intended as an open platform for public debate and discussion of political and social issues.[4] He initially tested the idea through the establishment of the German Student Party (Deutsche Studenten Partei, or DSP) at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art on 22 June 1967.[5] Founded by Beuys, his Master student Johannes Stüttgen, an artist Bazon Brock, the DSP was closely linked to student movements in West Germany, which had been growing in opposition to nuclear armament, the Vietnam Conflict, and the urgent need for education reform, and had been catalyzed by the shooting of a student during a protest in West Berlin earlier that month.[6] Lacking the Marxist-orientation of concurrent youth protests in other European cities or the United States, Beuys’ group was markedly spiritual in focus and embodied the artist’s growing interest in political ecology. Their goals included disarmament; a unified Europe governed by autonomous political, economic and cultural spheres; the dissolution of the use of East and West Germany as a political tool in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union; and “new perspectives” in education.[7] However, it was more successful as a platform for Beuys’ utopian thought than a political tool — he used their meetings and press coverage to propose that his concept of social sculpture could be applied to the broader German political arena rather than enacting any discernible revolutionary change.

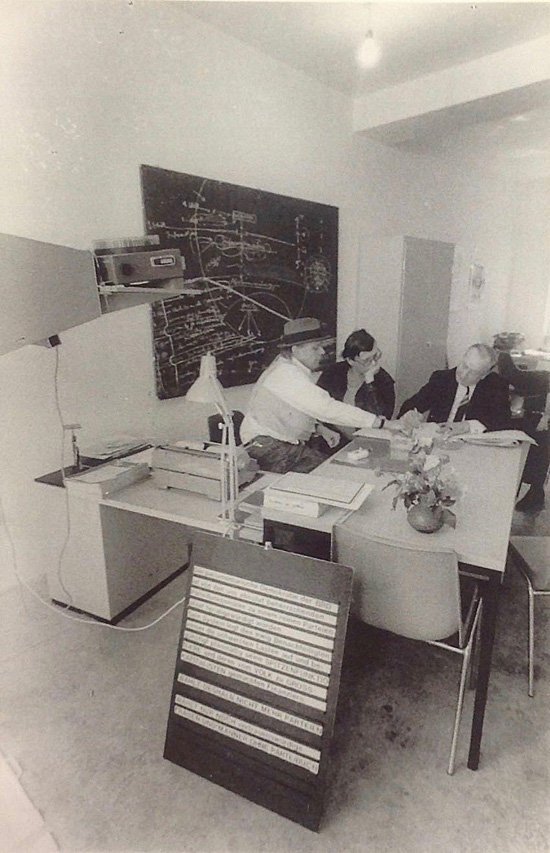

Beuys’ went on to promote a similar ecologically conscious agenda through the organizations and social networks he founded in the early 1970s.[8] The artist established the Organisation für direkte Demokratie (Organization for Direct Democracy, or ODD), a storefront meeting place aimed at citizen-initiated legislation, as a further expression of his concept in 1970 (it was later presented at documenta 5 in 1972). The purpose of the ODD, as Beuys stated, was to educate average people about the working process of the democratic system and how they might avoid engaging with the dominant political party system.[9] While they initially discouraged citizens from voting in elections as a means to break the “dictatorship” of the party system, Beuys and his team of assistants, which included Stüttgen and political activist Karl Fastabend, used their office in Düsseldorf to urge a broad cross-section of the public to enact their own legislative referenda through a direct democratic process.[10] Posters were hung in the windows encouraging passers-by to take brochures or engage in conversations and “working groups” that addressed the types of decisions they might make through referenda including education reform, women’s rights, and the protection of the environment. These issues were at the same time anti-war, pro-gender equality, markedly Marxist in orientation (albeit bathed in Beuys’ spiritual rhetoric), and focused on the environment — concerns that predominated Beuys’ public discourse from this point forward. However, like the DSP, the ODD turned out to be just another type of performance used to draw audiences to his ideas, rather than a viable attempt to institute a political alternative.[11]

The artist found yet another arena for his political thought with the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research (FIU), which he organized with a group of collaborators in 1973.[12] Through their activities, Beuys introduced his plans for an alternative pedagogic system based on the advancement of creativity over skills that was free from state control. The school, which was intended to cater to all people regardless of artistic talent, developed creativity through interdisciplinary research including psychology, communications, information theory, and perception teaching, accomplished through a mobile learning system consisting of educators from a variety of disciplines teaching as guest lecturers.[13] This way of learning was inherently international and promoted green ideals. They even planned several satellite schools, including an ecological institute and an institute for evolutionary science, which focused their research on biological needs, environmental research, and ecology, to evaluate existing social and economic structures and develop new possibilities for the future. The school was expected to open in Düsseldorf in April 1974 (although this iteration was cancelled); over the next few years it spread to other cities within West Germany (Achberg, Hamburg, Gelsenkirchen, and Kassel), and elsewhere in Europe including in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Italy. FIU workshops were held in conjunction with Beuys’ installation Honigpumpe am Arbeitsplatz (Honey Pump at the Workplace) at documenta 6 in 1977 on various topics such as nuclear disarmament, media manipulation and alternatives, human rights, labor and unemployment, and migrancy. Hundreds of participants from all over the world and from a variety of professions took part, embodying the concept of “unity in diversity” that would later be promoted by Beuys and the other founders of the West German green movement.[14]

Beuys was finally able to unite his lifelong interest in the natural world, animals, and botany with his concept of social sculpture when the environmental movement began to gain momentum worldwide in the mid-1970s. His cause dovetailed nicely with the increased support for the environmental movement in West Germany, which grew alongside larger social protest movements such as the student movement of the late 1960s.[15] Numerous citizens’ organizations dedicated to environmental issues emerged across the country during this period, partly in response to the environmental destruction caused by postwar industrialization.[16] However, the seeds for the green movement were sown when environmentalists, conservative ecologists, and left-wing radicals united in their response to the nuclear issue.[17] Beuys’ “Appeal” helped catalyze the movement, for in it he made no distinction between capitalist and communist ideologies in terms of handing out blame. Instead, he proposed a new form of politics to remedy this crisis situation that would restore freedom, creativity, solidarity, and mutual affinity and invited movements such as ecological groups, women’s liberation, gay liberation, civil rights, citizen’s initiatives, humanist liberalism, Christian sects, and democratic socialism to join forces, setting in motion a new democratic state in the 1979 European elections. While the ODD and FIU were founded as grassroots initiatives, their combined effort made it possible to directly engage in politics through the establishment of referenda and operation in higher political structures like the German Bundestag.

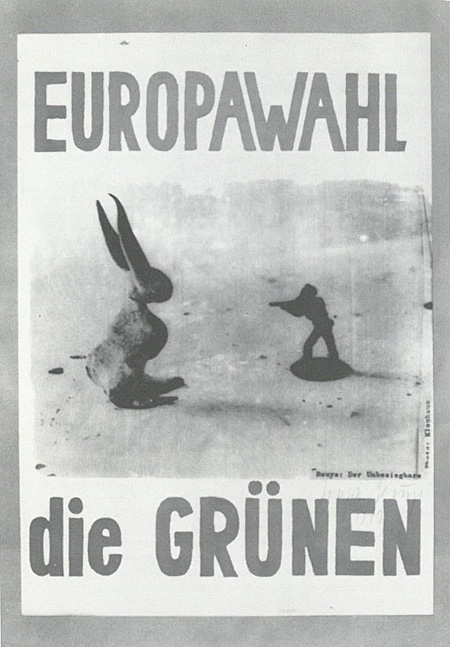

The coalition of alternative groups became Die Grünen (the Greens, or the Green Party), a political organization with a human-centered agenda concerning not only with the protection of nature and the awareness of environmental concerns, but also a new sense of political efficacy.[18] The point of connection between the coalition members, according to Beuys, was their relationship to a broadened definition of ecology that included economics, law, and the concept of freedom.[19] In January 1979, he met the young sociologist Lukas Beckmann and the two began plans for such an ecological group in the studio he occupied at the Düsseldorf Academy. The Greens were intended as an organization for the future structure of the social order, founded under the auspices of the FIU.[20] However, they quickly crystalized into a political party at a meeting in Karlsruhe in January 1980, as political pragmatism took precedence over the varying competing goals of the groups that made up the party. Beuys initially took a leading role alongside other career politicians who shared his views, although this phase was short-lived. Beuys never considered himself a professional politician, although he did run for office several times. He unsuccessfully ran for parliament in 1976, but he wasn’t able to gain traction as a viable candidate until the media began to pay serious attention to the Greens.[21] In 1979, the artist positioned himself as a Green candidate in the European Parliament election and later in the state election in North Rhine-Westphalia.[22] During his campaign, he produced a poster featuring a work from 1963, The Invincible, a small sculpted hare facing off a toy soldier with a gun. Through these “toys” he was setting his concept of social sculpture, harking back to the spiritual symbolism of the hare, in opposition to nationalistic military aggression (which here could be either capitalist or communist).

The coalition of alternative groups became Die Grünen (the Greens, or the Green Party), a political organization with a human-centered agenda concerning not only with the protection of nature and the awareness of environmental concerns, but also a new sense of political efficacy.[18] The point of connection between the coalition members, according to Beuys, was their relationship to a broadened definition of ecology that included economics, law, and the concept of freedom.[19] In January 1979, he met the young sociologist Lukas Beckmann and the two began plans for such an ecological group in the studio he occupied at the Düsseldorf Academy. The Greens were intended as an organization for the future structure of the social order, founded under the auspices of the FIU.[20] However, they quickly crystalized into a political party at a meeting in Karlsruhe in January 1980, as political pragmatism took precedence over the varying competing goals of the groups that made up the party. Beuys initially took a leading role alongside other career politicians who shared his views, although this phase was short-lived.

Beuys never considered himself a professional politician, although he did run for office several times. He unsuccessfully ran for parliament in 1976, but he wasn’t able to gain traction as a viable candidate until the media began to pay serious attention to the Greens.[21] In 1979, the artist positioned himself as a Green candidate in the European Parliament election and later in the state election in North Rhine-Westphalia.[22] During his campaign, he produced a poster featuring a work from 1963, The Invincible, a small sculpted hare facing off a toy soldier with a gun. Through these toys he was setting his concept of social sculpture, harking back to the spiritual symbolism of the hare used in previous performance pieces, in opposition to nationalistic military aggression (which here could be either capitalist or communist). The artist also became ubiquitous in the media — and this time not solely for his success as an artist, but for his political beliefs and activities.[23] Although he failed to be elected, Beuys continued to play a role in the Green Party throughout the early 1980s, as they became a more significant factor in the German party system by debating a variety of previously neglected issues such as ecological concerns, nuclear armament, and equal rights.[24]

While his actions were decisively political, Beuys never fully subscribed to any ideology, and therefore his participation conflicted with those who wanted to develop a unified agenda as well as a strategy to win elections. He worked closely with Green politicians such as Beckmann and Petra Kelly, but he eventually ran into the same ideological arguments that he found within capitalism and communism as the party began to integrate itself into the established parliamentary system. Although many of Beuys’ concerns coincided with those of the Greens, he was still dedicated to art as a means to transform society for the better, as well as the harmony between the human and natural worlds. The more the Greens operated as political party, the more they separated from the ideals Beuys had promoted through his own political activities, such as the DSP and ODD. His utopian vision, which was focused on individualism, and the political praxis of an alternative party, which requires a unity of purpose, were at odds from the beginning.

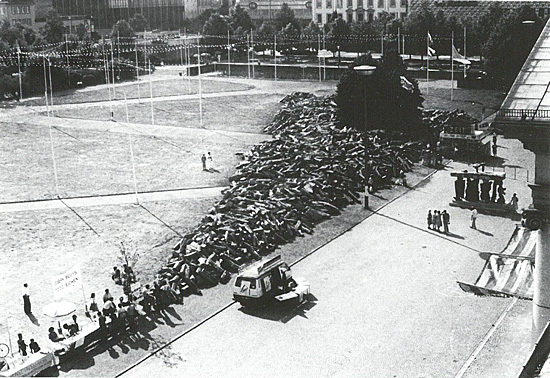

Perhaps as a result of his estrangement from the party, Beuys began to envision an environmental project with the potential to disseminate his theory of social sculpture to a worldwide audience: 7000 Eichen (7,000 Oaks, 1981–1987), which he proposed as his contribution to documenta 7 in late 1981.[25] The conception of 7,000 Oaks owes much to Beuys’ involvement with the Greens and his attention to biological and environmental issues.[26] For this action, he suggested planting 7,000 trees and accompanying basalt stone columns within the city limits under the motto “Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung” (meaning roughly “a forest-like city instead of city administration”). He requested that the residents of Kassel propose sites and plant the trees themselves alongside his team of city planners, gardeners, and environmentalists. The planting of the trees, which began in 1982 and concluded following the artist’s death at documenta 8 in 1987, was intended to replenish the lack of foliage in the city caused by the Second World War.

Beuys conceived of the trees and stones as emblematic of the ideas he was presently working with: social regeneration, creativity, liberation of individual thought from the present social order, ecology and environmentalism. The oak tree had specific relevance rooted in Germany history and mysticism, while the basalt stones were linked to the local landscape and Beuys’ expanded theory on art.[27] During the exhibition, steles were placed in a large triangular plaza in front of the Museum Fridericianum, on the Friedrichsplatz, awaiting placement next to an assigned tree. As each stone was removed and installed beside its tree, the pile symbolically marked the duration of the project and the exhibition itself. Beuys intended the work to be a monument that exemplified by the play of proportions between the trees, the steles, and the site. The basalt columns dominated the oaks as saplings, but would gradually be overtaken as the trees grew. At the same time, the stones remained a constant element — unchanging compared to the gradual growth of the tree.

The work was intended to be the most expansive project initiated by Beuys to date. He explained his idea to Richard Demarco in March 1982: “I wish to go more and more outside to be among the problems of nature and problems of human beings in their working places. This will be a regenerative activity; it will be a therapy for all of the problems we are standing before.”[28] The trees and accompanying steles served as symbolic markers for Beuys’ environmental cause, as well as the power of creativity and imagination to transform the planet. However, in order to initiate this process, individuals and organizations needed to consider their own responsibility in enacting global environmental change by participating in the project. Thus, 7,000 Oaks was the result an individual or local effort that radiated beyond the initial site. With his project in Kassel, Beuys envisioned the global diffusion of social sculpture — and indeed the physical remains of his project can still be seen not only throughout Germany, but also in Norway, Australia, and in several locations in the United States. Standing next to streets and in alleyways, in car parks and playgrounds, and marking peace, friendship, and the effort of all those that donated money, time, energy and expertise, the trees and stones are an ever-present reminder of Beuys’ ideals. He was able to transform the city from one covered in asphalt and tar into his vision of Verwaldung — an area completely covered by greenery. While it is hard to measure the success of his project aside from the popular affection for trees themselves, 7,000 Oaks has inspired many adaptations, commemorations, and homages led by artists, musicians, environmental activists, and art historians worldwide.[29]

With the rise in notoriety of socially engaged and participatory art forms since the 1980s, Beuys has emerged as a central figure for artists interested in a radical notion of ecology in terms of its application to both social and natural systems. According to art historian David Adams, Beuys was a “pioneer investigator of the role of art in forging radical ecological paradigms for the relationship between human beings and the natural environment.”[30] Such ideas coincided with artists in the United States, in particular, whose political projects were increasingly research based, site specific, and contextual, and those who were interested in converging their environmental concerns and political activism with artistic practice. Although domestic mentors and models of participatory art also inspired their work, these artists can be compared to Beuys in their use of art as a vehicle through which politics can be approached aesthetically.

Artists who have acknowledged Beuys as a precedent in their work include Mark Dion, who has been inspired by projects like the FIU to incorporate interdisciplinary research into installations that address the ways that nature has been represented in museums and in popular culture (his use of vitrines calls to mind Beuys’ “environments”), and Mel Chin, whose collaborative project Revival Field (begun 1991) is an effort to renew the ecology of a former landfill in a similar effort to Beuys’ proposed project for Hamburg in 1983.[31] The artist has also been an important referent for eco-feminists such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who was awarded a Percent-for-Art commission to be the artist at the Freshkills Landfill in Staten Island as the site was detoxified and redesigned as a park in 1989. Her project, which is composed of several landscape elements including a cantilevered walkway and will involve the participation of millions of people who donate an item to be permanently embedded there, is intended to “flood our environmental infrastructure with creativity,” a goal that she shares with Beuys.[32] Beuys also became more significant as socially active artists considered their own role as performers within their projects. The artist emphasized that his life was increasingly considered a total work of art in itself through the use of similar materials in his “actions,” his recognizable costume of the felt hat and fishing vest, his ubiquitous presence in documentary photographs of his projects of social sculpture, and his masterful use of the media to generate an awareness of both his artwork and his political cause.

In the years since his death in 1986, Joseph Beuys has not ceased to cause controversy both within Germany and abroad, and this has overshadowed the significance of his anti-authoritarian opinions as well as his concept of social sculpture.[33] These aspects of his career are seldom discussed in the United States, where the focus of scholarship on the artist has remained focused on his gallery and performance art practice, despite renewed enthusiasm for the artist owing to the growth of social practice art in the past two decades. Beuys’ projects of social sculpture were models for future action, which collaborators such as his students and Green Party members have carried forward. He is an important reference for socially engaged artists because he presented a form of pedagogic activity that was politically engaged, counter-institutional, and centered on the empowerment of individuals through creative development. Moreover, he attempted to translate this into a global movement. The projects Beuys inspired, which focus on direct experience, and in some cases on the physical shaping of the landscape, hark back to his concentration on spirituality and the role of the environment in this transformation. Beuys provided a genus for their work with the term “social sculpture” and gave them tools for engaging diverse publics about a range of issues, including environmentalism and ecology. Their projects, which focus on direct experience, and in some cases on the physical shaping of the landscape, hark back to Beuys’ concentration on spirituality and the role of the environment in this transformation. This, no doubt, demonstrates the artist’s vanguard role in using art to address educational reform, inequality in democratic processes, and the destruction of the natural world.

Cara Jordan recently received a PhD in Art History from the City University of New York Graduate Center, where she specialized in postwar public art in the United States. Her dissertation, “Joseph Beuys and Social Sculpture in the United States,” explores the role of Beuys’ theory of social sculpture in socially engaged art in the 1980s and 1990s. Cara has taught at CUNY’s Hunter College, Kingsborough Community College, and City College, and has curated numerous public art projects in New York. She currently serves as editor of Peter Halley’s catalogue raisonné and works as a freelance editor in Berlin.

[1] Joseph Beuys, “Appeal for an Alternative,” Centerfold 3, no. 6 (September 1979): 307. Translation of an article published on 23 Dec 1978 in the Frankfurter Rundschau.

[2] Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1979), 7.

[3] Beuys quoted in Schellmann and Klüser, “Joseph Beuys, The Multiples,” 24. His approach to ecology has also been discussed in David Adams, “Joseph Beuys: Pioneer of a Radical Ecology,” Art Journal 51, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 26-34.

[4] He conceived of his work as “parallel processes” — his sculptures, performances, installations, and multiples on one hand, and on the other a “permanent conference.” — both of which were united under his expanded theory of art. His first major solo exhibition, Parallelprozess I, was held at the Städtisches Museum, Mönchengladbach, from September 13-October 29, 1967. This exhibition was the first of a numbered series of Parallelprozess exhibitions presented throughout 1968.

[5] Götz Adriani, Winfried Konnertz, and Karin Thomas, Joseph Beuys, Life and Works (Woodbury, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 1979), 88-89; Susanne Anna, ed., Joseph Beuys, Düsseldorf (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2008), 64-66.

[6] See Martin Klimke, “West Germany,” in 1968 in Europe: A History of Protest and Activism, 1956-1977, ed. Martin Klimke and Joachim Scharloth (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 97-110.

[7] Adriani, Konnertz, and Thomas, Joseph Beuys, Life and Works, 161-162.

[8] The following year, in 1968, his position at the Düsseldorf Academy was severely threatened not only because he engaged his own students in political organizing, but because he began lobbying for the autonomy of the Academy from state control. He was eventually fired in fall 1972 for his blatant disregard of the school’s admissions standards.

[9] Volker Harlan, Rainer Rappmann, and Peter Schata, Soziale Plastik: Materialien zu Joseph Beuys (Achberg: Achberger Verlag, 1976), 10.

[10] Although the group remained at the same location in Düsseldorf, the organization was officially renamed the Organisation für direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung (freie Volksinitiative e.V.) (Organization for Direct Democracy through People’s Initiative) in July 1971, emphasizing its focus on direct political engagement rather than a complete boycott of the electoral process all together and beginning a trajectory that led Beuys towards the formation of the Green Party in 1978–1979. Now registered as a nonprofit organization in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, the ODD published its first charter in August 1971.

[11] As neither an entirely political, cultural, or educational endeavor, his project lacked a focused audience. Outside of the space of the exhibition, press covering the project was rare, and the expected resonance of his project was never actualized. The ODD in Düsseldorf closed in 1980, but its mission has continued through the Omnibus für direkt Demokratie, established by Johannes Stüttgen, and the Mehr Demokratie e.V., run by Beuys’ former Green Party collaborator Lukas Beckmann, Gerald Häfner, Thomas Mayer, and Daniel Schily.

[12] Hans Peter Riegel, Beuys die Biographie (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2013), 392. The FIU was officially established after Beuys’ dismissal from the Academy at the home of lawyer and activist Klaus Staeck on 27 April 1973. At this meeting, roles were established amongst a small group of collaborators: Staeck became the chairman, Karlsruhe painting professor Georg Meistermann the deputy, journalist Willi Bongard the secretary, and Beuys the founding rector.

[13] Adriani, Konnertz, and Thomas, Joseph Beuys, Life and Works, 265.

[14] Once Beuys was no longer around to promote the mission of the FIU, the organization quickly dissolved. Its office in Düsseldorf closed in 1988, just two years after the artist’s death. It has continued to survive through the efforts of Rainer Rappmann, who continues to publish FIU and Beuys related books, pamphlets, and DVDs through the FIU Verlag, and several of Beuys former students, who established later iterations of the FIU in Amsterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Munich, and in South Africa (some of which still exist to this day).

[15] The movement emerged from conservation movements in the nineteenth century, but was catalyzed by the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962. Its translation and republication in Europe had widespread impact. Christopher Rootes, “The Environmental Movement,” in 1968 in Europe: A History of Protest and Activism, 1956–1977, ed. Martin Klimke and Joachim Scharloth (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 295-296.

[16] E. Gene Frankland, “Germany: The Rise, Fall and Recovery of Die Grünen,” in The Green Challenge: The Development of Green Parties in Europe, ed. Dick Richardson and Christopher Rootes (London; New York: Routledge, 1995), 25.

[17] Rootes, “The Environmental Movement,” 301; Frankland, “Germany: The Rise, Fall and Recovery of Die Grünen,” 23-24.

[18] Rootes, “The Environmental Movement,” 302.

[19] Beuys stated, “In my understanding, ecology today means economy-ecology, law-ecology, freedom ecology…we cannot stop with a kind of ecology limited to the biosphere…the ecological problem is a result of the unsolved social question in the last century. Therefore I say the only thing which [sic] works is again a sort of enlarging of the idea of ecology towards the social body as a living being.” Clive Robertson and Lisa Steele, “Sprechen Sie Beuys?,” Centerfold 3, no. 6 (September 1979): 311-312.

[20] Party newsletters that circulated in 1979 bear the stamp of the Green party and the FIU. “Newsletter on the Founding of ‘Die Grünen’ in Düsseldorf in January 1980,” December 14, 1980, JBA-B 004590, Joseph Beuys Archiv, Museum Schloß Moyland, Bedburg-Hau, Germany.

[21] Ulrike Claudia Mesch, “Problems of Remembrance in Postwar German Performance Art” (PhD Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1997), 324-325.

[22] An account of Beuys’ campaign activities can be found in Johannes Stüttgen, “Die Grünen,” Impressions, no. 27 (Spring 1981): 32–39.

[23] Beuys campaigned openly in the German media, including mass publications such as Der Spiegel, Stern magazine, and others. Mesch, “Problems of Remembrance in Postwar German Performance Art,” 325.

[24] The Greens gained national success in the 1983 Federal Elections, when they secured 5.6 percent of the vote and 27 seats in the Bundestag, and again in 1987 with 8.4 percent of the vote and 42 seats. This success was paralleled in the 1984 and 1989 European Elections. Thomas Scharf, The German Greens: Challenging Consensus (Oxford, UK; Providence, RI: Berg, 1994), 3.

[25] documenta 7, 19 June – 28 September 1982, curated by Rudi Fuchs. Beuys began planning 7,000 Oaks with Fuchs as early as November 1981, but the project did not officially begin until Spring 1982.

[26] Though nuclear armament and power remained a key Green issue, environmental issues became more prominent in the mid- to late-1980s due to media coverage of ecological issues, scientific studies on topics like acid rain, eco-disasters like Chernobyl, and local stories of toxic chemicals. Frankland, “Germany: The Rise, Fall and Recovery of Die Grünen,” 30.

[27] See Tisdall, Joseph Beuys, 72.

[28] Richard Demarco, “Conversations with Artists,” Studio International 195, no. 996 (September 1982): 46.

[29] There have numerous several iterations of the project in cities worldwide. In 1997, Christian Philipp Müller performed A Balancing Act during documenta X to address the quest for balance between social and formal in art. In 2007, artists Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey germinated 250 oaks from the original trees in Kassel for a project called Beuys’ Acorns, which has been exhibited in the UK and France since 2010. In 2012, the German-Canadian electronic group Knuckleduster committed to plant trees along their tour route in honor of 7,000 Oaks. Environmental activists also planted their own trees on the hill of Uisneach in Ireland.

[30] Adams, “Joseph Beuys: Pioneer of a Radical Ecology,” 26.

[31] Both artists cite Beuys as a precedent in their work. Chin even staged a mock lecture in the style of Beuys’ “public dialogues” for the conference Mapping the Legacy at the Ringling Museum in 1997. See Mel Chin, “My Relation to Joseph Beuys is Overrated,” in Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy, ed. Gene Ray (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc., 2001), 113-137.

[32] Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “A Journey: Earth/City/Flow,” Art Journal 51, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 14.

[33] “Kunstler Beuys, Der Größte Weltruhm Für Einen Scharlatan?,” Der Spiegel, November 5, 1979.