May 15, 2013

Discovering William Kentridge

Understanding politically engaged contemporary African art from a distance and how it may raise awareness about personal politics of location

Written by Srđan Tunić

INTRODUCTION: politics of location

At the time of the 51st October salon in Belgrade (2010), in which the highly acclaimed contemporary South African artist William Kentridge was being exhibited for the first time in Serbia, I had just started working in The Museum of African Art in Belgrade[1], charged with the task of conducting research on the artist[2].

In the attempt to construct adequate tools for analysing the artworks, and to develop an understanding (and empathy) towards William Kentridge’s art, one of the key challenges for me was to understand local and global perceptions of specific artworks in order to define which elements could be read specifically in a local context (and which therefore were clearer to “insiders”), and which could be termed “universal” (more or less recognised by “outsiders”).

Understanding the meaning and remembrance of personal narratives (memory) and the past –key topics of Kentridge’s art – as well as his works’ (g)local connotations and significance, necessitated a logical and deeper investigation into their political aspects. Among other things, this investigation revealed to me how Kentridge addresses (neo-) colonialism and apartheid through contemporary art, and hence how art can be a powerful tool to raise awareness about African history. Bearing in mind possible limitations when addressing history through art (defined by facts and “objectiveness”) and being in the position of a researcher who “translates” culture from a starting point located in “another” part of the world (Serbia), a place where African contemporary art in general has a very low visibility, this article aims to question the possibility of avoiding the neocolonialist trap in theory and practice. In other words: does my own personal “politics of location”[3] permit me to displace myself from the current, Western discourses in the field of contemporary African art?

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE AT THE 51ST OCTOBER SALON:

(re)presentation and contextualisation

Titled The Night Pleases Us..., the statement of the Salon (by Johan Pousette and Celia Prado) clearly declared its focus and an intention to bring together international and local perspective:

The individual choice, how to reformulate memory and the strategies about how to forget will be common denominators for the curatorial concept and the invited artworks to this year’s October Salon. The exhibition will visualise the conceptual statement through a selection of relevant international works of well-established as well as upcoming artists. In a sensitive, documentary and philosophical way it will focus on recent global history narrations parallel to the recent history in the Balkan region.[4]

The curatorial team both tried to develop a sort of ear for the local, regarding the matter of history and remembrance in contemporary Serbia, and to make a continuation of their previous project, the 2009 Gothenburg (Göteborg) International Biennial for Contemporary Art What a wonderful world. Retaining a poetical approach, the Gothenburg exhibition focused on the political aspects in art (individual and collective), while in Belgrade it kept the focus on the individual, “...but went further to the memories that influence our choices, the very sense of a stable self and identity”.[5] Belgrade Salon also included a site-specific intervention by opening a ruined building of the former Military Academy to the public as the exhibition venue, contributing to the layers of local memory, history narratives and site-specific artworks.[6]

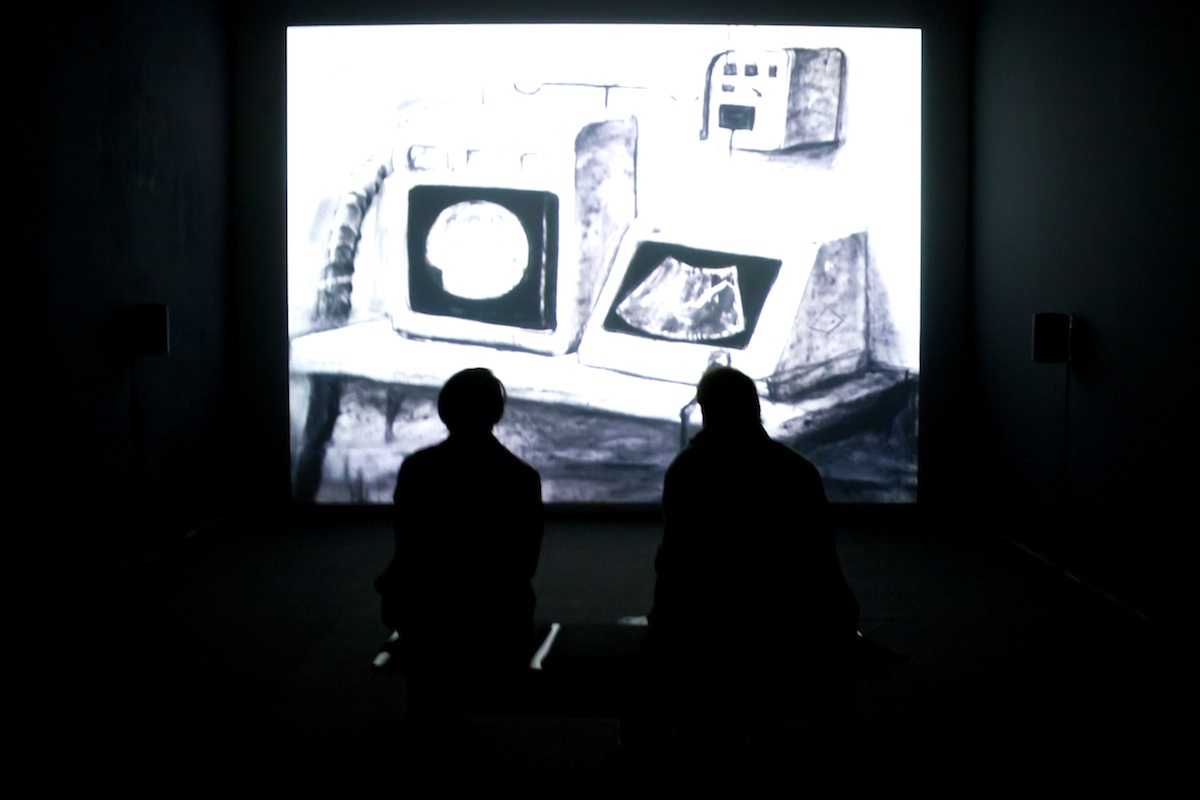

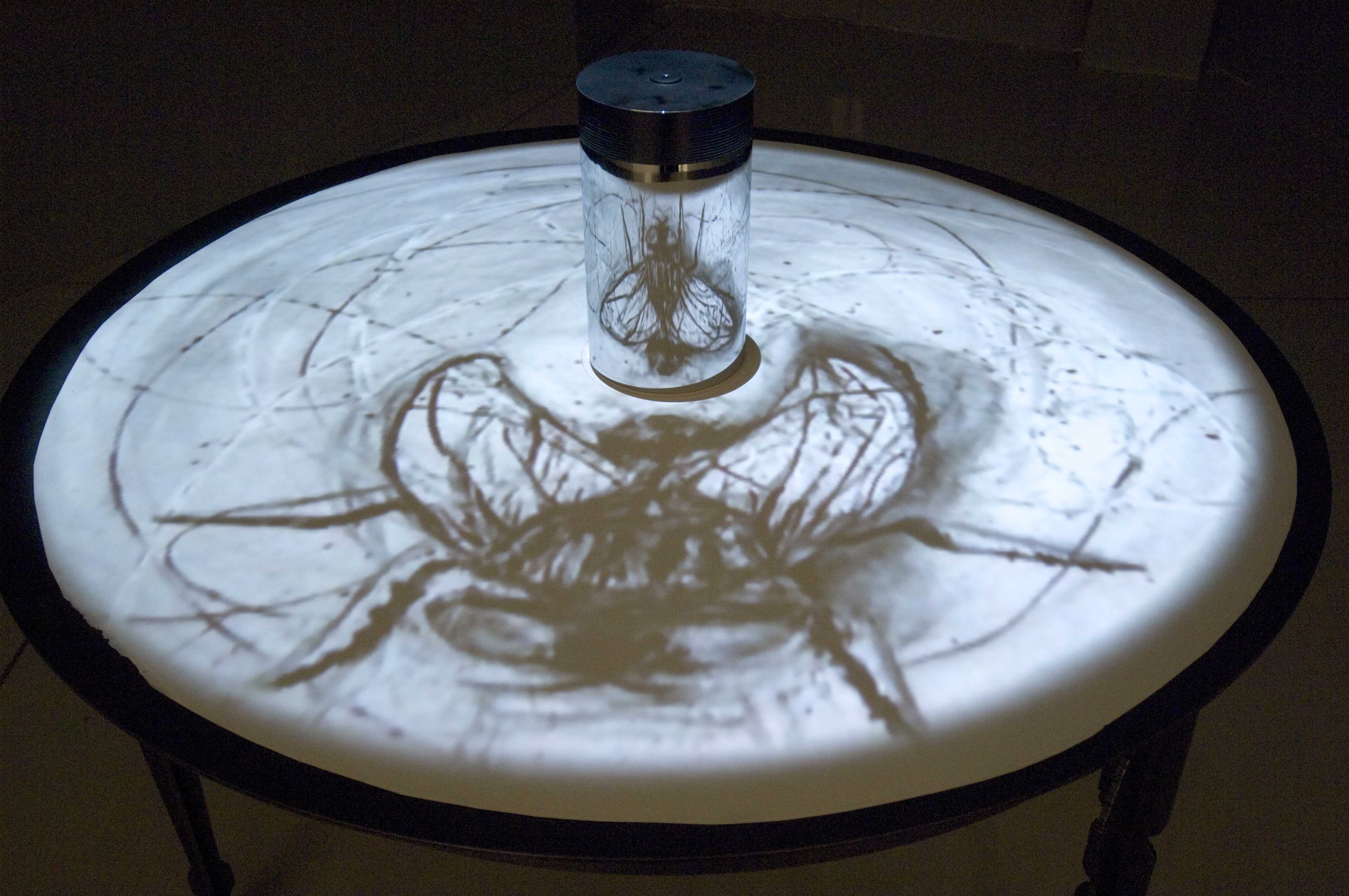

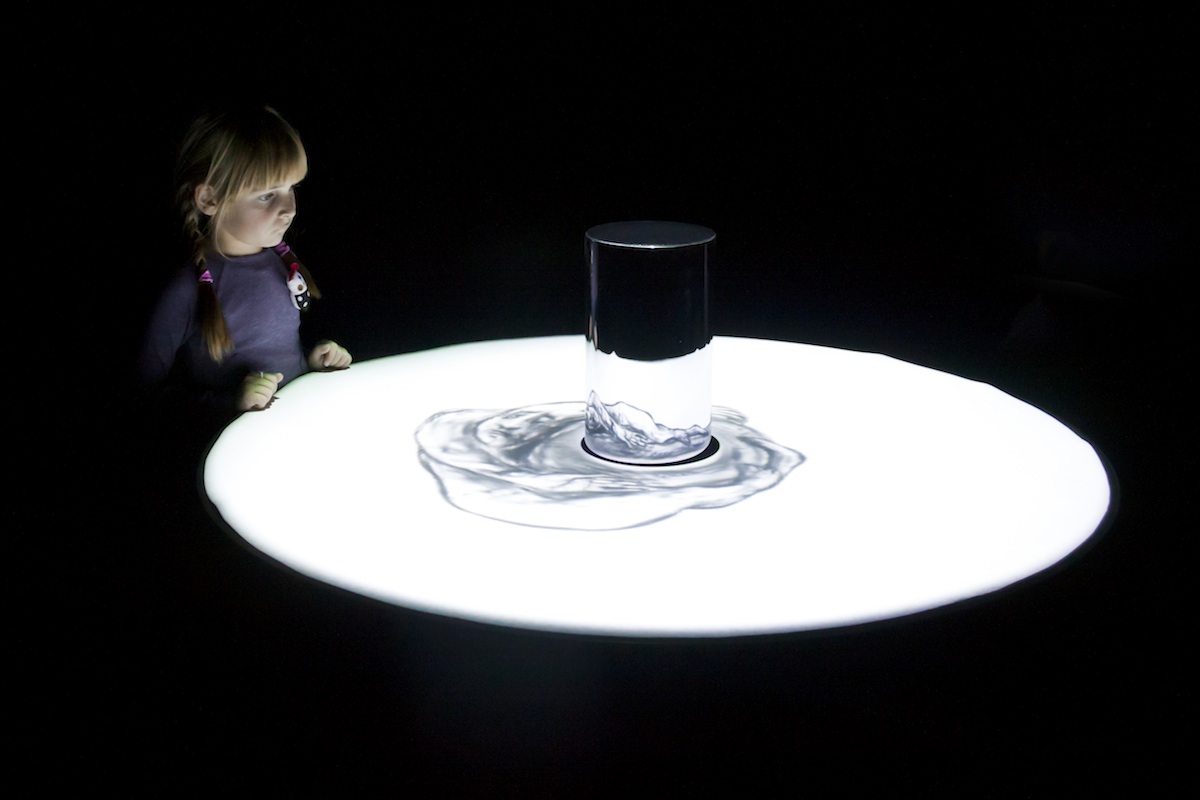

William Kentridge was presented at both exhibitions by his recent work What Will Come (Has Already Come) (2007), while the Belgrade exhibition also included a couple of earlier works: Johannesburg: 2nd greatest city after Paris (1989), History of the main complaint (1996) and Stereoscope (1999).[7] The artworks were divided into two dark rooms, one with a screening of earlier films (as a sort of introductory for an artist being presented for the first time in an international exhibition in Serbia) and the second as an anamorphic film/installation of What Will Come (Has Already Come), which gained the greatest focus and which was also the only work with an accompanying text in the Salon’s catalogue. With references to the work’s distinctive technique, and its linkage to colonialism in Africa (Abyssinia war 1935-6), in an interview with curator Pousette, Kentridge emphasised the political element of art as well as the understanding of history. Upon art making a difference regarding politics or social engagement, he answered:

I think (political art, S.T.) has a potency, as it always has had. If not to change people’s perception, but to confirm people’s perception of things they are uncertain of. How we construct ourselves out of things we read, things we have seen, generally confirms impulses that we already have, and strengthens them and shows that our perception might be a more broad thing... My art is not political in the sense that it has an instrumental end it’s trying to achieve. If politics is about the exercise of power, it (W.K. art, S.T.) is about the reflection of the exercise of power... Without understanding history, which is to say understanding that where we are now is not a static position but a process and the unfolding of something that began a long time ago, it is impossible to make sense of where we are now.[8]

This connection, between the curatorial (here possibly applied to both Gothenburg and Belgrade exhibitions) and the artist’s statements, is exactly where politics of location, as a perspective, comes in. For someone who got in touch with Kentridge’s art for the first time, the accompanying texts and setting did not provide a sufficiently clear understanding of the local contexts of South Africa (older works) and Ethiopia (newer work), to be able to properly analyse the artworks.

At the same time it is a challenge to define the political label on Kentridge’s art – which advocates ambiguity and contradiction, without one great story or perspective, focusing instead on intimate and multilayered artistic world and horizon.

LOCAL/GLOBAL – CENTRE/PERIPHERY

The selection of an artwork dealing with colonialism and genocide carried out by Italian fascists in Ethiopia just before the WWII was clearly motivated by an urge to draw parallels between the recent history in the Balkan region, in particular the war in Yugoslavia during the early 1990s, and an international context (described in the curatorial statement). It is arguable whether this war, a constant topic in contemporary Serbian (and Balkan) art, represents a “hot topic” or a stereotype (coming from “outside” curators) for actual politically engaged art of Western Balkans (ex-Yugoslavia countries), but it surely gave enough grounds for establishing parallels between the remembrance of a conflict and genocides in the Balkans and Eastern Africa.

The potent creative interpretation of an artwork such as What Will Come (Has Already Come) is based on its political function as it interacts with local history in several places at the same time, attracting my interest in the environment and history of the artist’s origin, as well as making me become aware of my own. Within the curatorial concept, several artists from the Balkans, incorporated in the Salon, emerged as direct references of the idea outlined above – establishing parallels in addressing (incomplete) memory and reinterpretations of (suppressed) history, both personal and collective. The curatorial statement itself opens the possibility of merging “foreign” and “local” meanings, thus encouraging parallels between various artists selected for the Salon. It is important, before addressing specific comparisons in question, to pinpoint the strategy of Kentridge’s art of remembrance. I advocate that it consists of three important segments:

1) Transformation of the outer and inner world through animation, by using realistic, surreal and metaphorical style of visual presentation, and technical inconsistency of the presented “objects”

2) Speaking about history without manifest and explicit political symbols, through fragments and associative means (narrative), and

3) Focusing on the individual memory, life, feelings, and stories, both universal and locally rooted

Within this frame, several strategies of remembrance could be discussed connected with other artists dealing with history and memory presented alongside with Kentridge at the 51st October Salon in Belgrade. Most of these strategies place historians in a rather difficult position, when trying to establish references and “objective” historical knowledge. However, tangible both as intangible knowledge, heritage, as well as personal memories make an enormous contribution towards understanding one’s specific time and place, both historical and contemporary.

As far as addressing personal memory is concerned, Ana Adamović’s work Canzona (2010) stands as the milestone of the Salon. Making a part of the series Madeleine, it deals primarily with the theme of old age and memories that stretch for a life span, by making an en face photographic/video portrait of an old lady listening her own performance of a favourite canzona (song) from youth. While the observers are faced directly with the image and gaze of the elderly lady, it opens a space for an emotional world and making us involved to experience and emotions. Main “protagonists” in Kentridge’s artworks – Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitelbaum – function also as a human source of reference, empathy, storytelling, in establishing a connection with the observer. However, in contrast to Adamović’s work, they present both fictional and real people, archetypes and Kentridge’s alter egos.

When discussing the “discovery” of history, or rather paying attention to its forgotten or alternative paths, apart from Kentridge’s What will come..., examples could be drawn with several artists of the 51st Salon. Zoran Naskovski’s Death in Dallas (2000-2010) functions as a documentation of “alternative” memory, combined with video recording of the murder of John Kennedy and playing a record from the ‘60s. In this work, Naskovski uses the narration of a Serbian traditional musician playing gusle (string instrument) who, through an epic poem, addressed the contemporary event from his personal viewpoint, whose record was “discovered” decades afterwards. In line with this “saving” attempt of personal memory and forgotten history, are Harun Farocki’s work Respite (2007) which resurrects the films made for a Nazi concentration camp and Carl Michael von Hausswolff and Thomas Nordanstad’s video Hashima, Japan (2002), depicting an abandoned island which was a promising mining site a century ago.

Upon looking on Kentridge’s specific technique of narration –adding and erasing the charcoal’s trace, in order to achieve the animation made from drawings – we see an element of evasiveness. We could notice blurry traces of previous drawings, fragments of objects, humans, architecture, landscapes, functioning as a reminder of past motions and a vague memory. The most appealing counterpart to this element of Kentridge’s art is the video installation Three rooms (2008) by Jonas Dahlberg. In 26 minutes a realistic representation of three domestic rooms in black and white degrade, dissolute and leave just a vacancy defined by the lights and the walls. This slow and silent process of disappearing and playing with our memory was achieved by melting paraffin, modeled after real-life furniture and everyday objects. Dahlberg’s works focuses on the process, without protagonists to narrate or underline the “message”. Dušica Dražić’s The winter garden (2010) and David Maljković’s These days (2005) produces similar, yet different documentary clashes between historical memory and the present.

The culture of remembrance plays one of the key parts of the Salon, as well as for William Kentridge. Amar Kanwar’s work The lightning testimonies (2007), through multiple video installation views, faces the visitors with archives of testimonies of women’s sexual violence in India. On the other hand, Steve McQueen’s work – the installation Once upon the time (2002), which documents the Voyager II spacecraft’s images of human life, launched in 1977 by NASA to go beyond the Solar system – is focusing on saving the knowledge for the future.A possible and interesting comparison could be made in trying to juxtapose South Africa’s apartheid and Yugoslavian civil war, from an artistic lens. Maja Bajević’s Women at work-The observers (2001) and Aernout Mik’s Scapegoats (2006) play with reconstructing history and references/memories of the 1990s war. Especially Scapegoats have a strong comment on the ambivalences of the war – by avoiding to advocate “sides” other than the those who control and those who must obey, without nationalistic or political symbols. This attitude sets alongside with Kentridge’s avoidance of using manifest political statements, focusing on the protagonists’ story – often, without a definitive “story”.[9]

In understanding local contexts and outlining similarities between Serbia during the war and South Africa during apartheid, I suggest that one more key point needs to be addressed – and that is that both societies were under international sanctions. This situation could be investigated through two examples present in Kentridge’s art: 1) local slang and subtle references are hard to read from an outsider’s standpoint, since they were not entirely present in the official media (such as Casspir riot vehicles metaphorically presented in Johannesburg: 2nd greatest city after Paris) and 2) besides great shocks and massacres, the widely present inwardness of “ordinary” people, best illustrated in Kentridge’s charcoal films from 1989 till 1999 such as mentioned Johannesburg, Felix in exile (1994), History of the main complaint, Weighting... and wanting (1997) and Stereoscope, targeting the relation of main characters Soho Eckstein (with his wife) and Felix Teitelbaum. Also, at the moment of political and social rejection, being the “periphery” of contemporary art world, a worthy comparative research between South African and Serbian (still bearing the name Yugoslavia at the moment) society might prove interesting, at least in understanding the possible parallels and differences that might come up.

“Centre” in this case, as opposed to “periphery”, might be articulated as a notion of using the “other” as cultural interest, the subject to be translated and integrated into the mainstream (e.g. the Western dominant culture). This position of a society being in a process of transition can also prove correct the tendency for generating “critical outsider” and “alternative” in the described context.[10] Nonetheless, curator Dan Cameron states that the political transformation of South Africa sets it apart from other so-called post-ideological transformations (counting in Yugoslavia, too).[11]

Here, I would also like to mention a couple of burning questions for future research: are there any specific developmental influences from the global art world in the reception (and selection) of African contemporary art in Serbia today? Has African contemporary (and in general non-European) culture and art had any influence whatsoever in the period following thebreakout from the old Yugoslavia?Stable connections were present since the 1960s as Yugoslavia was part and a great supporter of Non-aligned movement (the first Non-Aligned conference was held in Belgrade in 1961), but since the 1990s the contact has been weak. Tour of bands (“world music”) and traditional and contemporary artistic events may arise from time to time (organised by a few African embassies, public institutions or individual initiatives), but one of the key points in analysing the presence of African culture in Serbia (and the region) are the activities of The Museum of African Art in Belgrade (MAA).[12]

For example, the presence of contemporary African artists such as Barthélémy Toguo in 2006 in Belgrade, as part of an initiative Coloured world of Belgrade’s artist Mihael Milunović, was a great opportunity to establish direct contact with the artist and his work, providing an insight into his art through an exhibition Transit(s). First part of the exhibition, consisted of Toguo’s documentary works made during a three year period (1996-1999) where he enacted a series of performances named Transit(s), based on lingering/enduring stereotypes which are attributed to the foreigner / outsider. The exhibition space was covered, for this occasion, with cardboard from transport boxes. His statement says: We are all in permanent transit. This is a notion inherent to man living in the 20th and 21st century. The colour of one’s skin is insignificant: whether white, black or yellow, everybody is potentially exiled, being driven by an engine called travel, consequently becoming a migrant.[13] A new artwork, developed for this exhibition, was a site-specific installation in the MAA’s dome floor. This installation articulated local references, based on museum’s artifacts which were made available for the artist, and was titled The Hommage to Zdravko Pečar, dedicated to the founder of the museum. Forming a “boat” of museum exhibits:

...ancestor figures, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sculptures, baskets, vessels, calabashes, drums, weapons, contemporary memorabilia such as cushions fashioned from industrial fabric that portray postcolonial west-African presidents and more than 20 animal skulls – hunting trophies of Zdravko Pečar, the „great hunter“ and Museum benefactor – were placed on a cardboard runway ready to take off, or saie away towards the Danube and further. Liberated from the approach to objects that dissects them in their „passports“ (or museum identification slips) into place of origin, material, function – Barthelemy Toguo creates amazing arrangements and makes unexpected links, gathering these museum exhibits – envoys of the African continent – in sets that they have never previously been arranged in.

Adding a deeper layer of understanding and playing with the role of a contemporary African artist as well as with museum clichés, Toguo’s installation questions his own African identity and makes a statement of ambivalent choices and free interpretation.[14] However, this remains a singular (rare), not a practice that is systematically (even politically) practiced.

The visibility of African contemporary art and culture (apart from mostly exotic touristic stereotypes) is rather occasional, although I believe that Serbia’s re-involvement with the Non-aligned movement (currently being an observer country) and having a constant flux of international students since 2011 would give way to establishing more direct exchange of artists and cultural professionals. Crno telo, bele maske (Black body, White masks) by Dejan Sretenović, curator of the Museum of contemporary art in Belgrade in 2004,[15] stands as one of the rare exhibitions dealing primarily with postcolonial theory, the translation of traditional African art and culture for the West and analysing Yugoslavia’s involvements (social, political, cultural) with Africa.

THE USE OF WILLIAM KENTRIDGE IN LOCAL CONTEXT

In the text above I have tried to outline briefly the key points of my research on Kentridge’s art, as well as the understanding of the context I consider vital in trying to raise questions about my personal politics of location as a viewer of Africa and African art from a distance. Understanding (global) art – both past and present – is a constant process where the observer has an active and versatile role, defined both socially and individually.[16] Insofar as my personal process of translation of William Kentridge’s art is concerned, my intentions were to have as deep of an insight as I could, from a distance. The possibilities of promoting my research were spontaneous,driven by potential educative elements of Kentridge’s art, and resulted in lectures (William Kentridge: the art of remembrance – Students’ cultural centre, Petnica – history students’ seminar and summer camp lectures on political contemporary African and Kentridge’s art), film projections (William Kentridge: Postcolonial South Africa's fragments of memory – Yugoslav Film Archive Kinoteka) and texts (AFRIKA – studies in art and culture, Journal of the Museum of African Art, Number 2). At some points I got the impression of addressing a rather “exotic” subject, since I mostly encountered people not familiar with African contemporary art at all. Therefore, I understood that my professional role was to present a relevant context, as well as the artist himself – being informative and professional. Having in mind that the research is politically and culturally conditioned, and has (g)local social consequences, an extra need for self-reflexion is required where the concern also becomes ethical.[17] The view aware of both local and global context which I was trying to achieve was reinforced as a sort of reaction (activism?) to my own context: The wish to present an (artistic) view from the “outside”, non mainstream art world of Serbia, trying to overcome the stereotypes (as surviving neo-colonialism) and nurture empathy.

Special thanks to Emilia Epštajn for professional support.

Srđan Tunić, from Belgrade, Serbia, is an art historian and a freelance curator, interested in promoting and developing understanding of non-European arts and cultures in Serbia. Together with colleague Andrej Bereta as co-author, he works on curatorial research and the educative project Kustosiranje / About and around curating located in Serbia and the Balkan region.

[1] The Museum of African Art: The collection of Veda and dr Zdravko Pečar: www.museumofafricanart.org/ My work, as a curatorial associate and animator/educator, lasted from summer 2010 till autumn 2011.

[2] Vilijam Kentridž na 51. Oktobarskom salonu (William Kentridge on the 51st October Salon 2010), in Serbian and English, June 2011 (AFRIKA: the studies of art and culture, issue #2, the Museum of African Art, Belgrade, spring 2013, forthcoming).

[3] Further analysis of politics of location in researching in Beyond the Personal: Theorizing a Politics of Location in Composition Research, by Gesa E. Kirsch and Joy S. Ritchie, College Composition and Communication, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Feb., 1995), National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, pp. 7-29.

[4] www.oktobarskisalon.org/51/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9&Itemid=17&lang=en, www.kcb.org.rs/Programi/Likovniprogram/LikovniNajave/tabid/1086/AnnID/931/language/en-US/Default.aspx Curatorial statement of Johan Pousette and Celia Prado, the 51st October salon, Belgrade (retrieved on 05.03.2013).

[5] The Night pleases us... A conversation between Johan Pousette and Celia Prado, curators of the 51st October salon, and Charlotte Bydler. The 51st October salon catalogue, The cultural centre of Belgrade, 2010, pp. 16-17. http://goteborg.biennal.org/en/about-biennial/history/2009/what-a-wonderful-world (retrieved on 03.03.2013).

[6] The building was supposed to house the Museum of the City of Belgrade after the Salon, but still remains ruined and without a clear function. The similar process of transformation (physical, social, imaginary) of a ruined space into active place was achieved with the former building of Geodetic institute in Belgrade, on the 53rd October salon 2012 titled GOOD LIFE: Physical narratives and spatial imaginations. More info in the catalogue, curatorial Introduction by Branislav Dimitrijević and Mika Hannula, The cultural centre of Belgrade, 2012. Available online at http://www.oktobarskisalon.org/53/concept/?lang=en (retrieved on 05.03.2013).

[7] More in: Vilijam Kentridž na 51. Oktobarskom salonu (William Kentridge on the 51st October Salon 2010), ibid.

[8] William Kentridge in conversation with Johan Pousette, 2009. The 51st October salon catalogue, The cultural centre of Belgrade, 2010, pp. 96-97.

[9] The night pleases us..., The 51st October salon catalogue, The cultural centre of Belgrade, 2010.

[10] More on discussing contemporary political art in Serbia, its ideological, philosophical and aesthetic implications in Dissensus Communis — Savremena umetnost kao politički označitelj više (Dissensus Communis - Contemporary art as political signifier more) by Branislav Dimitrijević, forthcoming.

[11] A procession of the dispossessed, Dan Cameron, in Wiliam Kentridge, C. Christov-Bakargiev, D. Cameron, J.M. Coetzee, W. Kentridge, Phaidon, London 2010, p. 39.

[12] The South African culture was directly present from 2009 to 2011 through the collaboration of the MAA and NGO Makhaya arts and culture development, organising Africa village art, cultural, touristic and economy events, which continues occasionally until the present moment. In 2011 the event South Africa – Meeting Point featured an exhibition of contemporary art that toured Vienna (Austria), Budva (Montenegro) and Belgrade, selected by curator Bongani Mkhonza. Online: http://www.africavillage.eu, http://www.museumofafricanart.org/en/activities/international-cooperation/145-south-africa-meeting-point.html (retrieved on 05.03.2013).

[13] http://www.museumofafricanart.org/en/programs/coloured-world/148-transits-2006-barthelemy-toguo.html (retrieved on 22.04.2013).

[14] Transit(s) and Hommage to Zdravko Pečar: exhibition and installation by Barthelemy Toguo, by Emilia Epštajn, in AFIKA: studies in art and culture – journal of The Museum of African Art, issue #1 (ed. M. Lukić-Krstanović), Belgrade 2009, pp. 109-112. Online: museumofafricanart.org/images/magazine/ASKUMAU_no01_2009.pdf (retrieved on 05.03.2013)

[15] Crno telo, bele maske (exhibition and catalogue, in Serbian) by Dejan Sretenović, Muzej afričke umetnosti (The Museum of African Art), Beograd 2004.

[16] Sociologija umjetnosti (The sociology of art, orig. Sociologie der Kunst), by Arnold Hauser, parts „Umetnost i povjesnost“ (knjiga I, 71-82) and „O umjetničkom doživljaju“ (knjiga II, 11-15), Školska knjiga, Zagreb 1986.

[17] Beyond the Personal: Theorizing a Politics of Location in Composition Research, ibid, p. 25.