December 29, 2015

The Aesthetics of Identities and the Difficulties of Histories: The Contemporary Chinese Southeast Asian Art

Written by Nobuo Takamori

Ethnic Chinese: Definitional problems

Among the difficulties encountered in discussing Chinese Southeast Asians is the lack of a workable definition which, inevitably, involves the dimensions of sanguinity and culture. Both dimensions are embedded in different social structures of Southeast Asian countries, and their connotations vary accordingly. Moreover, there may be a world of difference as to how other ethnic groups define the Chinese communities and how different Chinese communities define one another. As a result, we should not regard the subjects discussed in this article - Chinese Southeast Asians – as a single, unified ethnic group.

Since the fifteenth century, Southeast Asian countries have attracted a large number of Chinese immigrants, including different dialect groups speaking in Hokkien (Southern Min Language), Hakka, Cantonese, and Hainanese, among others (it was not until the post-war era that the Mandarin Chinese flourished under Kuomintang’s continuing influence). Possessing their own cultural attributes and social structures though, these heterogeneous immigrant groups have assimilated thoroughly into the local cultures in the centuries-long history of immigration. For example, the Peranakan Chinese who live on the Malay Peninsula have mixed the Malay language with Hokkien vocabularies as a lingua franca despite the traditional Chinese customs they preserve. Filipino nationalist José Rizal is ethnic Chinese by descent but maintains a quite different cultural identity. (José Rizal is a pioneering writer who insisted on writing in Tagalog language for the purpose of highlighting Filipino nationalism.)

Both Peranakan Chinese and José Rizal’s family were not the “real Chinese” in the eyes of the Chinese communities who immigrated to Southeast Asia between the late nineteenth century and the mid-twentieth century. As far as these Chinese Southeast Asians were concerned, the Chinese identity was a question not only about sanguinity but also about the sustainability of languages and culture. However, such a perspective has been confronted with monumental challenges in the post-war era. The Chinese culture was deliberately suppressed in the newly emerging Southeast Asian nation-states within whatever bloc during the Cold War period. One result of this is that only a very small population of Chinese Indonesians speaks fluent Chinese languages nowadays. Chinese Indonesians have also been forced to name themselves in an “Indonesian style.” At the same time, in the eyes of other ethnic groups in Southeast Asian countries, Chinese communities still exist even though they have assimilated fully into the local cultures. As a consequence, Chinese Southeast Asians (whether they speak Chinese or not) have no way of circumventing the identity of “ethnic Chinese.”

As far as Chinese Southeast Asian artists are concerned, identity not only involves introspective exploration of individuals, but also has much to do with the relationship between individuals and societies. An easily neglected, important point is that the identities their artworks take on are ergo not only political in nature, but also microcosmic incarnations of politics.

Available Options of Political Identity: Two Chinas or a New Nation

The Chinese cultural identity involves not only languages, religions, dietary habit and lifestyle, but also the connections with the Chinese dynasties embedded in the Confucianism order. On a more specific basis, both the ruler-official relationship and the clanship with the family of origin imply a matter of ethics in the Chinese culture. The ethics may not be renounced with the emigration from China to other countries, which was why Chinese Southeast Asians had used the year numbering system of the Qing Dynasty in their quotidian existence and on their tombstones throughout the nineteenth century. Since 1911, Chinese Southeast Asians had handled their relationship with the newly established Republic of China from the perspective of previous dynastic traditions. Malaysian artist TAN Kian Ming (陳建泯) recorded numerous Second Sino-Japanese War Monuments erected on the Malay Peninsula. His artworks suggested that the constructors of these monuments regarded themselves as nationals of the Republic of China. As far as they were concerned, the Pacific War was not so much a war fought between the United Kingdom and Japan as the extension of the Sino-Japanese War.

The massacre of ethnic Chinese (the intelligentsia in particular) carried out by Japan during its occupation of Southeast Asia has become a common historical trauma for Chinese Southeast Asians. However, Japanese imperialism had deliberately fostered Burmese and Indonesian autonomous governments and cultures, which indicated the differentiated treatment that Japan meted out to different ethnic groups in this region. This differentiated treatment had a far-reaching influence in the post-war era. Singaporean painter LIM Yew Kuan (林友權, 1928) created Night Arrest in the 1950s, depicting the family tragedy that struck when Japanese troops arrested his brother. Making a powerful combination of painting, performance and video, Malaysian artist WONG Hoy Cheong (黃海昌, 1960) created Sook Ching (肅清, the Cantonese pronunciation of the massacre carried out by Japanese troops) in the 1990s. Both artworks drew on the survivors’ experience of the massacres perpetrated by Japanese troops; however, they respectively insinuated the political atmospheres prevailing in the times of their creation. The British colonial government’s elimination of Malayan Communists reached its climax in the 1950s. The Japanese soldiers in Lim’s work were not dressed in regimental uniform, which was reminiscent of the highly charged political atmosphere that pervaded the country in the 1950s. On the other hand, Wong’s artwork finished in 1989 evoked strong associations to the Operation Lalang in 1987 in which the Malaysian government not only ordered the mass arrest of opposition party members and social activists but also imposed a ban on newspaper publications.[1]

Chinese Southeast Asians’ struggle for identity construction had become intensified and complicated in the post-war era. They first of all faced the obligation to define their identities as nationals of either the newly emerging nation-states or of the Republic of China. After the Chinese Civil War and the Nationalist Party’s (KMT Party) retreat from mainland China to Taiwan in 1949, however, Chinese Southeast Asians were also forced to take sides between Taiwan (controlled by the Chinese Nationalist Party) and mainland China (controlled by the Chinese Communist Party). The artwork National Language Class by CHUA Mia Tee (蔡名智, 1931) [2] clearly represented one of the identity choices made by Chinese Southeast Asians at the critical crossroads in the history of their sustainability. This work visualized the thought of the intellectuals who espouse Malayan neo-nationalism. The young people portrayed in this painting are ethnic Chinese by descent. They concentrate fully on learning to speak Malay, the national language of the new Malaya. In the 1950s, the fate of Chinese Southeast Asians was affected by three forces that resulted in the disappearance of the pre-war homogeneity inherent in the Chinese communities dwelling in different newly emerging nation-states, which therefore prompted these Chinese Southeast Asians to weave their distinct historical narratives based on the development of their residential countries. The three forces came respectively from China, Taiwan (The Republic of China), and the United States. In the 1955 Bandung Conference, China made clear that Chinese Southeast Asians were nationals of Southeast Asian countries rather than those of China, which not only cut the long-term political and cultural umbilical cord that connected Chinese Southeast Asians to China, but also promoted the Republic of China in Taiwan to play the role of the “motherland” for Chinese Southeast Asians. Following the policy formulated before 1949, namely treating overseas Chinese as its nationals, the government of the Republic of China attracted a large number of Chinese Southeast Asians to study in Taiwan. Dr. CHOONG Kam Kow (鍾金鈎, 1934) who studied fine arts in Taiwan in the 1950s and profoundly influenced the development of Malaysian modern art served as a stellar example.[3]

TSAI Ming Liang (蔡明亮, 1957), an iconic figure in the film history in Taiwan, is a Chinese Malaysian. Among his tours de force, I Don't Want to Sleep Alone (2007) is the only work that shows his attempt to portray his homeland, Malaysia, a country which is unfamiliar to him. Another artist, Midi Z (趙德胤, KYAWK Dad Yin), who was born in Myanmar in 1982 and immigrated to Taiwan later, has been an active director in Taiwan recently. His works primarily focus on the real-life conditions of Chinese Burmese. The two examples starkly highlight the difference between the identities of the two Chinese Southeast Asian directors who work and live in Taiwan and belong to different generations.

The repercussions of American cold-war strategy spilled over from Taiwan and China to Southeast Asia. In Singapore, a group of students in Chinese middle schools launched a student movement on 13 May 1954. [4] After the independence of4 1Singapore in 1965, the Chinese Communist Party was condemned by the Singaporean government for inciting the movement and extending its influence over Southeast Asia through the system of Chinese language education. Based on this assertion, the Singaporean government began to shut down Chinese schools and promote English as the official language. Similar language banishment measures were implemented in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and other Southeast Asian countries. The consequence became apparent in the disorientation of young Chinese Indonesian artists whose works faithfully exhibited their unquenchable thirst for a sense of identity. Indonesian artist Tintin Wulia expressed her confusion over identity and nationality by directly employing passports as the creative material for her installation. The works by budding Indonesian artist Yaya Sung (Yaya Sungkharisma) were mainly inspired by the term “Banana Man” she encountered in Shanghai. The term refers to the ethnic Chinese who grow up in Western countries. What left her more confused was the fact that Indonesia does not even belong to the Occidental.[5] Starting from the work Unfamiliar Roots (Walking Banana), she used to address the memories and traumas brought by the May 1998 Riots of Indonesia, the mass violence toward ethnic Chinese. Against this background, she has tried to develop a broader perspective on Indonesian art and society through her recent artworks.

The Heterogeneous Chinese Communities Isolated from the Chinese World

The international society tends to use “diaspora” as the keyword to explain the present predicament that Chinese Southeast Asians are caught in. However, this issue has received surprisingly little attention in the history of Chinese Southeast Asian art. A plausible explanation for this outcome occurred to us when we treated Chinese Southeast Asians as the subject of this article. Chinese Southeast Asian artists inevitably have to devote a greater deal of effort in constructing their subjectivity in the newly emerging nation-states. In addition to their involvement in ethnic politics, they have to reflect on the modern history of their countries and the thorny issue of nation-building. For example, Malaysian artist CHONG Kim Chiew (張錦超, 1975) attempted to explore the history of New Villages through his work Isolation House created in 2005. During its conflict with Malayan Communists, the British colonial government believed that a pro-Communist attitude prevails among Chinese communities, and ergo arbitrarily relocated the ethnic Chinese living in the countryside to the militarily-controlled, prison camp-like “New Villages”. The British government remains reluctant to apologize for such a conduct to date. In his recent project Boundary Fluidity, Chong manifested the complex history of Malaysia by repeatedly drawing and modifying the map of this country layer by layer and meanwhile by writing different toponyms on the same locations.

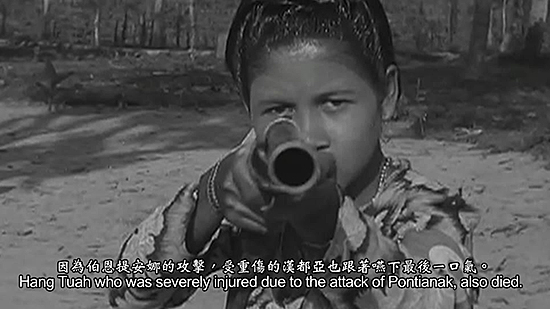

AU Sow Yee (區秀詒, 1978), a Malaysian artist who lives in Taiwan, has also focused on exploring the collective identity and history of Malaysians. In her work A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (2013), she fabricated the place named Mengkerang as a tropic utopia in Southeast Asia. In addition to juxtaposing real and fictitious documents in the exhibition venue, she produced a pseudo-documentary by inviting her friends from different ethnic groups who speak in Hokkien, Mandarin Chinese, English, and Malay to fabricate the utopia where different ethnic groups co-exist harmoniously. In her work Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others (2015), Au ostensibly narrated myths yet actually insinuated the history of Malayan Communists’ struggle for power by collecting common folk legends shared among different generations of Malaysians and editing historical documentaries and other types of films.

The examples considered in this article featured the artists who assume Russian doll-like identities as Southeast Asian and Chinese. I also know many artists from Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Indonesia. They do not necessarily identify themselves as Chinese even though they have partial Chinese ancestry. Similarly, some Taiwanese artists born in Laos, Brunei or Malaysia do not identify themselves as Southeast Asians without any trouble. Difficulties thus arise when we try to position these artists’ works and narratives in the context of Chinese Southeast Asians. In fact, the existence of Chinese communities, along with their special historical and political roles, relies heavily on the indication given by other ethnic communities. For example, few artists attempt to discuss the issues regarding Chinese identity, history, and cultural construction in Singapore where ethnic Chinese form the majority of the population. Chinese Southeast Asians are heterogeneous Chinese communities isolated from the Chinese world, which is why Chinese Southeast Asian art has been excluded from Chinese Art, even though the latter has been identified as a major trend in the global contemporary art scene. We can neither understand the situation and art of Chinese Southeast Asians by reference to China’s point of view, nor grasp the historical status and identity of Chinese Southeast Asians by investigating the newly emerging nation-states in post-war Southeast Asia. Nevertheless, the existence and the subjectivity of Chinese Southeast Asian art is essentially necessary for our inquiry because they serve as an invaluable reference not only to the political complexity and difficulty that haunted post-war Southeast Asian nation-states but also to the cultural manipulation in the cold-war strategies and the construction of ethnic identities. All of these count as critical links for understanding the modern history of Southeast Asia.

Nobuo Takamori is a PhD Candidate in the Institute of Applied Arts at the National Chiao Tung University of Taiwan Hsinchu. Takamori is also a Curator of Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts in Taipei National University of the Arts, Director of Outsiders' Factory, a curators’ collective, and member of the Southeast Asia Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Culture of Taiwan.

Takamori’s curatorial works include “Post-Actitud” (2011, Ex Teresa Arte Actual, Mexico DF), “South country, South of Country” (2012, Zero Station, Ho Chi Minh City & Howl Space, Tainan), “The Lost Garden” (2014, Eslite Gallery, Taipei), Taiwan International Video Art Exhibition 2014 “The Return of Ghosts” (Hong Gah Museum, Taipei), “I Don’t Belong” (2015, Galleria H., Taipei) and “Wild Legend” (2015, Jumin Museum, Jinshan).

[1] See CHAI Chang Hwang, WONG Hoy Cheong and His Liberated Art (in Mandarin Chinese), 2007, http://arty-arty2.blogspot.tw/2007/09/wong-hoy-cheong.html.

[2] See Singapore National Gallery’s collection: https://www.nationalgallery.sg/collection/artwork-detail/P-0145/national-language-class

[3] See CHAI Chang Hwang, A Study on the Subjectivity of Malaysian Chinese Painters (An Outline), in Imagining Identitues: Narratives in Malaysian Art. Edited by Nur Hanim Khairuddin, Beverly YONG.

[4] 1954 National Service riots.

[5] See Yaya Sung’s personal website: http://www.yayasung.com/unfamiliar-roots/