The Return of the Political and Art Censorship

Written by Lidija Marinkov Pavlović

Two unusual scenes and two conventional reasons for a ban connect the artistic concepts which were censured, a year apart, in two major centres of European culture and art. Those are Brett Bailey's Exhibit B in the Barbican Center in London in 2014 and Christoph Büchel's art project The Mosque, which represented the Icelandic Pavilion as part of the Venice Biennale in 2015. The scenes represent a few dozen people whose gathering initiated the events of different intensity and character, while the reasons for the ban were defined as measures against security threats. Before we analyse the actual cases of censorship, we should ask the following question: what actually appears in the structural place of the visibility of contemporary art which was vacated in the name of the legal system, human rights, moral paradigms and even in the name of protecting the security?

1. Penetrations of the visible

Today, censorship appears as a radical intervention of power that regulates the eventing, the performance or the construction of the visible and its context and meanings, in an attempt to fence off, reclaim, i.e. reterritorialize the political space that it can manage. However, in the long history of formal or external censorship, aesthetic values have never been expressed as direct criteria for banning. The framework of legal definitions, but more often of the ideological apparatus, especially in societies where censorship is not legally regulated, implies prohibitions that should protect the morals, religious dogma, national interests and nowadays, the security order. This means that the issue of censorship is closely related to the production of a modern social subject that recognizes the sovereignty of the state in exchange for the protection of its rights and freedoms. Therefore, for example, article 19 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, even though not legally binding, proclaims the aspiration towards a total freedom of expression, as well as the defense of this principle on a universal level. Paradoxically, the defense in the name of "all members of the human family" (Preamble) implicitly and unavoidably infers the exclusion of others.

From this perspective, the aporias of freedom of expression and autonomy of art is resolved precisely on this critical point of intersection of the concept of Kantian aesthetic-disinterestedness art from which its autonomy is derived and indirect reasons for censorship within the so constructed autonomous field of art. In other words, the very fact of censorship intervention and its hegemonic powers in the field of art suggest that art is not independent from social rules nor autonomous in relation to the practical policy of regulating sociability. The autonomy of art, in which the power is hidden in order to conceal or censor the political, can actually appear as an inherent autocensorship of the political of/in the art.

The policies of consensus in the contemporary post-democratic and post-secular societies in which the neoliberal order is represented by the populist authorities, result in a sharp split between politics as principles of the organization of society and the power that realizes social relations. Politics loses its politicality and increasingly becomes a technique of formal management. The traditional elements of politics, such as the parliament or public opinion, are no longer capable of representing different social identities and antagonisms – today they are transparently and dominantly realized in the field of culture and art. Numerous and loud demands for the bans of certain artistic works are made increasingly more often by bottom-up movements which build their value judgments or identity positions through the negative attitude towards the parts of institutionalized art practice. On the other hand, one should have in mind that every censorship is realized from the position of power and that there still exists a censorship from the top, justified by the "reasons of the state".

The penetration of the visible, which becomes the object of censorship in conteporary post-political societies, can point toward the uncertainty and, in the final instance, the contingency of the global order. In the sense of activism, one might therefore speak of the politization of art in which the artistic event itself discloses the phenomenon of social antagonism (Šuvaković 2012: 82). Therefore the analysis of the censorship of artistic practices today includes the analysis of procedures and strategies in conteporary art that structure the political field of the visible within complex and variable dispositions. This also means that art still has the power to show, construct and perform actual social movements that later mobilize different communities.

Jacques Rancière differentiates two logics of human being-together: police and politics. The police denotes a system under which a certain collective is gathered and unified, and which then legitimizes the assignment of places, functions and power within such a configuration. According to Rancière, in order for the police system to survive, it is foremost necessary to define the configuration of the perceptible. That means that the police is firstly an order of bodies, i.e. a system that enables certain bodies to be named, to have their place and their mission: "it is an order of visible and sayable that sees that a particular activity is visible and another is not, that this speech is understood as a discourse and another as noise." (Rancière 1999: 29) As opposed to the police, politics denotes an activity that destroys the established perceptible configuration of parts and parties and, importantly, the cessation of the established order brought forth by the appearance of parts of those who have no part: "Political activity is whatever shifts a body from the place assigned to it or changes a place’s destination. It makes visible what had no business being seen, and makes heard a discourse where once there was only place for noise." (Rancière 1999: 30) As a result, the political practice suggests the effort to confirm the contingent equality of all, i.e. all the beings that speak. According to Rancière, politics is, therefore, an acting practice whose principle is equality, but from the point of political philosophy, the difficulty arises from the aporia brought forth by the rationality of politics itself, which is the rationality of disagreement. In a nutshell, by "disagreement" Rancière implies a certain type of a fully concrete speaking situation in which the speech of the other party is both understood and not understood. The radical disagreement produces a situation in which one of the interlocutors cannot see the common reference, i.e. the object of the dispute itself.

2. Politics, power and the space of appearance

In a somewhat broader framework, the censorship procedures significantly impact the relations in the public sphere, so the analysis usually includes different contexts in which the censorship is made or which it creates on its own. From a modernistic paradigm, according to Hannah Arendt, the power is the one that holds the public space as a potential space of appearance in which people can speak, act and reach a consensus. When constituted, a public space is organized in different forms of government. (Arendt: 199-207) However, that power does not source from antagonistic conflicts, but the ideality of the consensus is achieved through reciprocal exchange of voices and doxas within the social plurality. (Mouffe2013: 18)

Jürgen Habermas also foresees a public place in which a consensus can be reached, but the necessary requirement is the exchange of logical arguments, a rational discourse taking place under the assumption of fulfilled democratic rights and freedoms that allow communication, as well as free means of that communication. Formal or informal censorship has appeared, in the past, as it does now, as an intermediary technique that controls the social communication and introduces a social hierarchy. Chantal Mouffe notices that, in spite of significant differences, neither Arendt nor Habernas confirm the hegemonic nature of a consensus that predicts a necessary exclusion. Every pluralism is added to the horizon of the intersubjective agreement. (Mouffe2013: 18) Instead of the Kantian doctrine of aesthetic judgment, through which Hannah Arendt points to the procedure of determining the intersubjective agreement in a public space, Chantal Mouffe advocates for critical artistic practices by way of an agonistic approach. She believes that those who encourage the creation of agonistic public places understand critical art completely differently than those whose goal is to create a consensus. Compared to the agonistic approach, critical art is a collection of different artistic practices that point to the existence of alternatives to the current post-political order. "Its critical dimension consists in making visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate, in giving a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony." – Chantal Mouffe claims (2013: 77)

Together with Ernest Laclau, Mouffe believed, as early as the end of the 80s, that the political thought needs to take into account the ontological dimension of radical negativity close to the Lyotardian understanding of the irreconcilable antagonism (le différend). Therefore Chantal Mouffe stresses the difference between politics and political. Political implies a dimension of antagonisms constituent for the human societies, whereas politics denotes a set of practices and institutions through which the order is created and human coexistence is organized in the context of constitutive radical conflictions. (Mouffe 2005:9)

However, unlike Rancière who believes that the ethical turn of aesthetics and politics in the contemporary post-political order, besides erasing all differences, leads to contingent equality and inability of dissensus, which, finally, is the feature of the regime that Rancière calls aesthetic, Mouffe believes that any order is always the expression of the relation of power. The ontological dimension of antagonism cannot be dialectically overcome, but can be advocated through an agonistic model of democracy that does not negate the possibility of reaching a consensus, but rather predicts the approach to confrontation within democratic institutions, recognizing the "partisan" character of democratic politics.

3. Censorship and the politization of art

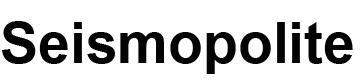

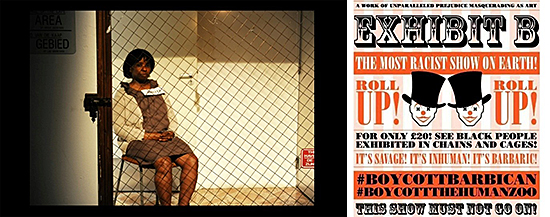

The artistic project by a South African interdisciplinary artist Brett Bailey, Exhibit B, was performed from 2010 to 2016 in many European festivals. However, the exhibit was cancelled in London in 2014. Exhibit B is an artistic project which uses multiple explicit and disturbing scenes and installations to show the consequences of racism, with an accent on dehumanizing methods, as well as their continuity which is well present even today, in the treatment of migrants. In connection with the performing of Exhibit B in Edinburgh, Lyn Gardner, a theatre critic for The Guardian, wrote: "It reminds us that most history is hidden from view; it reminds that Britain's 21st-century ways of seeing are still strongly skewed by 18th-, 19th- and 20th-century colonial attitudes." (Gardner 2014)

The controversy of Exhibit B stems from the actions of the artist, who reconstructs historical cases and traumatic places and scenes in the exhibition space, introducing performers with a silent interaction with the audience. Through a carefully determined procedure, choice of performers and a previous work with them, Bailey, in a sense, overturns the stereotypical objectification of a black body in the racist forms of representation into an emancipating event. That is further supported by witness statements of the performers themselves, which became the final part of the exhibition. On the other hand, the harsh reviews were made toward the outrageous repetition of racist discourse through the phenomenon of "human zoos", i.e. the insulting spectacle of the exotic body in a public space. This stems from as far as the 19th century circus shows with “monstrous” and different bodies. These shows are organized in a form of a spectacle, with the aim to affirm the "normal" body through difference, and with it, the normative identity of a member of the European bourgeois class. (Figure 1) The argumentation of the critics and activist in favour of the ban of Exhibit B, therefore, stressed the ethic criterion. Art, in the foremost, must not be offensive, so the white South African artist had to consult with the black community, the authority for this criterion. The artistic value can become the subject of debate only after the ethical criterion has been met.1

A public debate and a call for a cancellation and censorship of the announced performance of Exhibit B in London by the black activists was followed by a mass protest and blockade of the Barbican centre. The management of the Barbican could not guarantee the safety of the audience and the performers, so they cancelled the performance. The censorship act, demanded from the bottom-up in the name of human rights, enforced by the management of the Barbican for safety reasons, is paradoxical only at the first glance. The censorship has confirmed the power of the institution of art to manage and control the performance of the visible, as well as its social contexts and meanings, in an effort to regain its integrity.

It was the ethical demand for universal equality that does not admit the emancipating potential of the aesthetic that led to the paradox. In Rancière's terms, this event made visible the opposition between two types of violence and two types of rights (Rancière 2010: 185) However, at the moment when Exhibition B got suspended, the visible were the "noisy" protesters in front of the Barbican, which perpetuated the old order in the jurisdiction of the police. In other words, by censoring the performance, the management of the Barbican has (inadvertently) reconstructed the racist model of exclusion in a public place.

The Mosque project, created for the Icelandic Pavilion of the 56th Venice Biennale by the Swiss artist Christoph Büchel, was performed in the Catholic church Santa Maria dell'Abbazia della Misericordia. This church has not been used for religious practices for about 40 years, but it is often rented out for purposes of artistic exhibitions. Büchel, in cooperation with the Muslim Communities of Venice and Iceland, turned the space of a former Catholic church into a functioning mosque. So Büchel's The Mosque became the first mosque ever to be established on the soil of the city of Venice. The artist brought, among other things, the Muslim holy paraphernalia and schedules for organizing religious practices, into the Catholic church. Soon after the opening of the exhibition, members of the Islamic religion, members of the local Muslim community and also parts of the artistic audience of the Venice Biennale started performing religious rites in the space of the Icelandic Pavilion. At the same time, different types of discontent by the local population, as well as pressures by the government and Catholic church arose, followed by requests to close the pavilion. Even though the Icelandic Art Center insisted on it being an artistic installation and that, for example, the religious procedures of taking off one's shoes and covering one's head are not obligatory for the visitors of the pavilion, one of the many reasons the city officials named for the ban was the lack of the administrative license needed for an institutionalized performance of religious practices. Finally, after the estimate of the public safety board, the officials of the city of Venice decided to close the exhibition two weeks later. (Figure 2) As the actual reason for closing, they mentioned the overcrowding of the building, because the prayer gatherings overstepped the legal limit of 90 people.2

The curator team of the Biennale, headed by Okwui Enwezor, was conspicuously silent on this question. As Luiza Bialasiewicz well noted, not only that The Mosque project best reflects the proclaimed aims of the 56th Venice Biennale, but it fully conforms to what Enwezor earlier determined as politically successful artistic interventions. Namely, this kind of art is capable to "disturb the spatial coordinates of contemporary dwelling and place, rearticulating the ethical confrontation between the stranger and the neighbor, making space for a ‘temporary autonomous zone’[...] of encounters" (Bialasiewicz 2017: 383)

The Mosque project showed how the political activity that Rancière talks about works – by changing the purpose of a certain space. Doing that in a double way, The Mosque succeeds in making visible the community that the hegemonic historical-political order tends to suppress. However, this community could become visible only through the agonistic approach of the critical artistic practice. The later censorship enforced by the government indirectly confirms that the subversive potential of this artistic project was very well understood. This is further confirmed by the silence of the Biennale's curator team, whose conceptual framework was the actual subject of censorship. In other words, this is only superficially about a disagreement, i.e. whether the discussion about different institutional arguments was about the dispute about the subject of the debate itself – about the dilemma whether this is an artistic installation or worship. The official reason for the censorship act, the safety threat, directly shows that the hegemonic political order actually has the sovereign power to reterritorialize, reestablish the old configuration of part and exclude the ones with no part. This also means that the reconceptualization of public spaces does not necessarily lead to the rearticulation of social antagonisms, i.e. to the creation of meeting places where it is possible to reach a consensus. Censorship in this case shows that the construction of equality, equivalence and togetherness actually has a very exclusive and particular character.

4. Spectacularization of censorship and the return of the political

Both examples of the ban of the artistic practice have caused events that, at one point, erased the normative boundaries between art and politics. The permeability of these boundaries points to a double relationship of exchange that is established between politics and art. On that topic Miško Šuvaković claims: "By using politics, art becomes the instrument of establishment and performance of a social problem as a challenge to the normative order of power. By using art, politics becomes the instrument of spectacularization – becoming more visible, hearable – of a social problem that hides in the normative order of power, government, ruling." (Šuvaković 2012: 12) This citation holds a part of the answer to the question posed in the introduction to this text. However, in relation to the modern informational and communication strategies, which offer endless possibilities for visibility and transparency, and in relation to the contemporary order of perceptibility which has its biopolitical consequences, the suspension of the visible and censorship seem like critical points that can map a new articulation of power, politics and art.

At times of harsh political and economical situations, censorship changes its strategies, tactics and effects, and therefore indirectly influences the modified context in which the field of artistic practice is structured. Censored art works removed from public spaces, as well as debates led upon those events, are fully available today, in a digital environment. On one hand, the social antagonisms are spectacularized through an "event" of art in public spaces which reciprocally proves its inherent politicality. On the other hand, the visible itself, whose material presence has been removed from the public space by censorship, gets infinitely multiplied on the networks, repeating the proscribed images and contents. It is in that way exactly that censorship kick starts a spectacular visibility of social, political, cultural or aesthetic antagonisms.

In relation to the structural place where the suspension and production of the visibility in the artistic practices and systems takes place, one can talk about permanent political deterritorializations and reterritorializatons. In that process it often comes to a destabilization of an arranged order, its meanings and elements: rights, institutions and autonomies. In that sense, the return of the political points to a difference within the consensus characteristic for post-political or autocensored systems with conserved old, but empty forms, such as a political representation, but also to aesthetic-artistic canons.

There is a detailed archive that illustrates the public debate lead about the boycott and the final censorship of Exhibit B in Britain on the following web-page: http://thirdworldbunfight.co.za/exhibit-b/ Third World Bunfight is a South African art group within which Brett Bailey realizes his performances and installations.

After closing the exhibition, the Icelandic Art Center has publicly announced a list of rebuttals about the media reports covering the Icelandic Pavilion. This document is available at the following web-page: http://icelandicartcenter.is/news/important-corrections-regarding-media-coverage-of-the-icelandic-pavilion-at-la-biennale-di-venezia/

Lidija Marinkov Pavlović was born in Zrenjanin, Serbia. She completed an MA in Painting at the Academy of Arts, University of Novi Sad in 2001. She has exhibited her work in over 25 solo exhibitions in Belgrade, Novi Sad, Banjaluka, Kragujevac, Smederevo and elsewhere and in more than 100 group exhibitions in Serbia and abroad. Her works have won a number of awards in fine arts and extended media.

Pavlović currently holds a position of associate professor at the Department of Fine Arts in Novi Sad and is a Ph.D. candidate in the Interdisciplinary programme in Theory of Arts and Media at the University of Arts, Belgrade, as well as in the PhD programme in Fine Arts at the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad.

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah. (1998) The Human Condition, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, London.

Bialasiewicz, Luiza. (2017) ‘That which is not a mosque’, in: City, 21:3-4, 367-387, Routledge, London, New York.

Gardner, Lyn. (2014) Edinburgh festival 2014 review: Exhibit B – facing the appalling reality of Europe's colonial past, The Guardian, Aug.12, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/aug/12/exhibit-b-edinburgh-festival-2014-review

Mouffe, Chantal. (2013) Agonistics. Thinking The World Politically, Verso, London.

Mouffe, Chantal. (2005) On The Political, Routledge, London, New York.

Rancière, Jacques. (1999) Disagreement: politics and philosophy, Univerity of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Rancière, Jacques. (2010) Dissensus On Politics and Aesthetics, Continuum International Publishing Group, London, New York.

Šuvaković, Miško. (2012) Umetnost i politika, Službeni glasnik, Beograd.

Preamble of Universal Declaration of Human Rights, http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

Icelandic Art Center, Corrections Regarding Media Coverage of the Icelandic Pavilion, http://icelandicartcenter.is/news/important-corrections-regarding-media-coverage-of-the-icelandic-pavilion-at-la-biennale-di-venezia/

Third World Bunfight, http://thirdworldbunfight.co.za/